The one with shrinking structure (Part II)

In the last post we have been looking on to how size of data, specifically packet descriptors, impacts processing performance. As it turns out, reducing data size is really important in gaining speed. In today’s post I will try to present few additional, more aggressive and intrusive methods to further reduce structure size.

Know your data

Standard types like uint8_t, uint16_t are perfectly fine for most use cases. But if we know the exact range of possible values and want our data to be really compact, we can have more granularity by using bit fields and share bytes/words between few separate fields.

So what can we assume in our packet descriptor example:

- There is only so much physical ports possible on NIC. In this case 8 sounds as reasonable number (Napatech NICs from example can have up to 4 physical ports, 8 with some special wiring)

- Limiting ethernet frame size to 8k (13 bits) seems good enough

- 64-bit nanosecond timestamp is ~584 years, more than enough in most cases and definitely we could shrink it to some smaller size, like 48 bits

Of course those assumptions are not true in general case, but there are always some assumptions that can be made for a given application. Sometimes it makes application less future-proof. In case of limiting frame size, jumbo frames won’t work. And sometimes it makes it more complex. Like if we reduce timestamp size so much that wrapping around is possible we need to introduce some kind of logic supporting that. Therefore this should be always conscious decision, based on both measurements and common sense.

This is how structure with those new assumptions looks like:

struct PacketDescriptorWithAssumptions {

uint64_t timestamp : 48;

uint64_t size : 13;

uint64_t physicalPort : 3;

uint64_t* payload;

uint64_t payloadHash;

uint8_t isValid:1;

uint8_t flag2:1;

uint8_t flag3:1;

}

Unfortunately neither c++ standard nor gcc extensions have 48 bit integer types for x86 architecture, but bitfields works just fine here. Of course accessing and setting bit field values will be slightly slower than using basic integer types. Size of new structure is 25 bytes, so there were some minor savings. Processing performance is now 310 Mpps RX and 228 Mpps TX, so actually for TX we have performance loss, due to additional masking and shifting bits needed to access bitfields.

Tagged pointers

So how much more we can compress those descriptors? Is there any unused space left in their memory representation? It turns out it is, just not that obvious and available only under some conditions. For a moment let’s think how much information basic data types keep.

| Type | Bits of information |

|---|---|

| uint8_t | 8 |

| uint8_t* | 64 |

| uint16_t* | 63 |

| uint32_t* | 62 |

| uint64_t* | 61 |

Let’s explain that. uint8_t is simple, this is just an integer type, every bit is meaningful. For uint8_t pointer there is also nothing unusual. To be able to address every possible byte in memory, so with 1 byte resolution, every value of 64-bit pointer is needed. Interesting things start to happen with uint16_t*. To address those, only even memory addresses are needed, this is 2 bytes resolution and one last bit in pointer actually doesn’t hold any valuable piece of information. This is however with important assumption that data are aligned! It will not work for data which are, for example due to structure packing, unaligned. It is the same for 32 and 64-bit integers, here pointer resolution is 4 and 8 bytes (still, assuming aligned pointers). So in uint64_t aligned pointer there are 3 bits of information that can be used to store for example physicalPort. Memory representation of such pointer will look like that:

ddddddddd|ddddddddd|ddddddddd|ddddddddd|ddddddddd|ddddddddd|ddddddddd|dddddTTT

Where d is pointer data and T is “tag”, part of pointer we can use for other purposes.

Here is PacketDescriptor implementation using tagged pointer. Check source code for accessors extracting tag and pointer body:

struct PacketDescriptorTagged

{

uint64_t timestamp : 48;

uint64_t size : 13;

uint64_t isValid:1;

uint64_t flag2:1;

uint64_t flag3:1;

struct

{

uintptr_t payload : (sizeof(intptr_t)*CHAR_BIT-3);

uintptr_t physicalPort : 3;

} tagged;

uint64_t payloadHash;

};

uintptr_t is an unsigned integer type capable of holding a pointer. Putting it here allows using bit fields and makes casting to real pointer easier. Size of new structure is 24 bytes, so the savings were really miniscule. Processing performance is now 321 Mpps RX and 222 Mpps TX, so quite good. This is a little bit surprising, because accessing data members should be even more complex, and 1 byte reduction is not significant, but my guess would be that 24 byte size is now 8-bytes aligned, so much less unaligned reads and writes are needed.

“Stamped” pointers

Another trick that we can use, relies on architecture of x86 processors, so it is absolutely not portable. In theory on 64-bit machines there is 10^19 addressable bytes, which is 16 EiB (Exabytes). If we would have to address full range of memory we need full 64-bit pointer. In reality current 64-bit systems uses no more than 48 bits to address virtual memory (even less to address physical memory). You can check that by running:

cat /proc/cpuinfo | grep address

address sizes : 39 bits physical, 48 bits virtual

Using only 48 bits out of 64-bit pointer gives us whole 2 bytes of data to use! Amazing! But not so fast. Although those upper bytes in pointer are not used to store information, there are certain requirements they must fulfil. All 16 upper bits needs to have the same value as bit 47. This is called canonical address and if this requirement is not met, the processor will raise an exception. Handling canonical pointer will definitely cause some overhead in processing. Fortunately most operating systems assign only lower half of address space, where bit 47 is zero. This is another assumption, but let’s go with that. Name “stamped” was taken from implementation of this pattern in folly library

This is implementation using “stamped” pointer:

struct PacketDescriptorStamped

{

struct

{

uintptr_t size : 13;

uintptr_t isValid:1;

uintptr_t flag2:1;

uintptr_t flag3:1;

uintptr_t payload : ((sizeof(intptr_t)-2)*CHAR_BIT-3);

uintptr_t physicalPort : 3;

} tagged;

uint64_t payloadHash;

uint64_t timestamp : 48;

};

This way we have decreased structure size to 22 bytes. Processing performance is now 347 Mpps RX and 228 Mpps TX. This is the best result for RX processing so far, but still not that good for TX. So as usual, your mileage may vary, always measure and do not assume anything.

Summary

Using all described techniques I was able to reduce the size of structure from 48 to 22 bytes. Impressives over 50% reduction! This works great for memory usage, but not always that great for performance. Making data members unaligned and packing them to bitfields has its cost. Only doing careful measurements in specific use-case can answer which changes will actually improve performance. But it is always worth knowing that such possibilities exist.

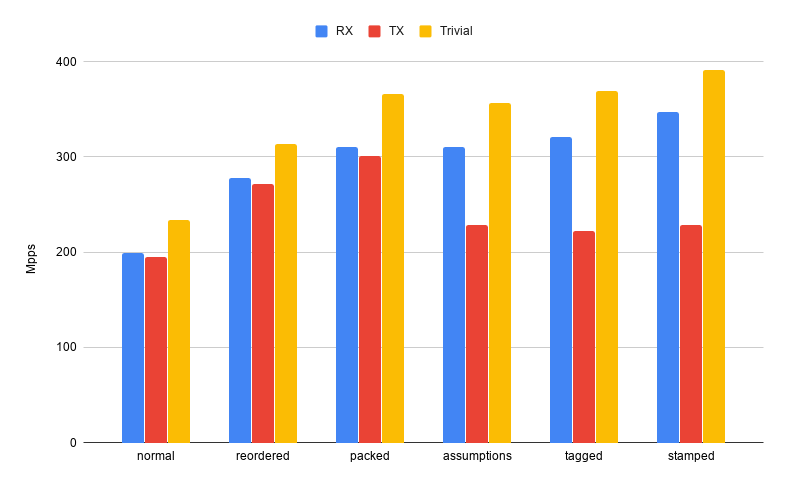

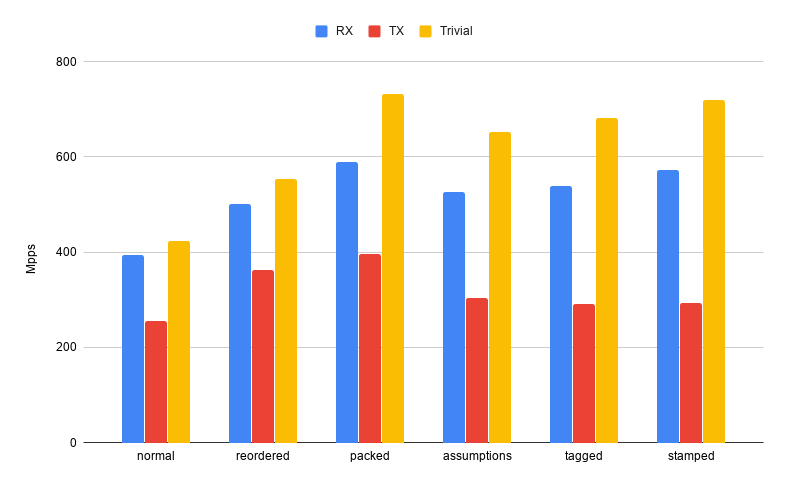

Below is a summary of results for all size reduction method presented in both articles. Additionally I have added “trivial” processing where only accessed field is size. This one should benefit the most form size reduction, as unpacking data is limited to a minimum.

Full results looks like that:

Server

Desktop

It seems that overall packed gives best performance, but for specific use-cases where processing is minimal, full blown solution with "stamped" pointers can also be used. I have another interesting observation here: performance of high-core server CPU is terrible compared to desktop CPU. It seems that single-core performance of server processors is quite limited and they are highly optimised for multi-threading.

The final working code presented in this post is, as usual on my GitHub.

Comments