The one with shrinking structure (Part I)

Nowadays real-world applications of C++ gets smaller and more specialised every day. It was decided almost by acclamation that business logic in new projects is written in higher order languages like Java, C#, Python or even something more sophisticated. But there are still areas where C++ shines: embedded and high performance.

To write high performance C++ code knowing language constructs is not nearly enough. Sometimes lower number of computations seen from the level of language (i.e comparisons, arithmetic operations etc.) gives slower code. Check this great talk by Andrei Alexandrescu to see how tricky it can be even for simple sorting algorithm.

There are also so many factors not modelled by language standard itself, like aggressive inlining, loop unrolling, link time-optimisation, vectorisation, intrinsics and builtins. And deeper there is yet another layer to performance optimisations: underlying hardware characteristics and architecture. This includes CPU architecture (x86, ARM, etc.), cache hierarchy, NUMA, SIMD, alignment. There are different techniques allowing to make use of hardware specifics. In this and few upcoming posts I will try to show few examples of optimizing high performance code to be more cache and memory friendly by reducing the size of data being processed.

Cache is the king

It is rather well known that one of the most important optimisation is making code cache friendly. One of the questions candidates might hear from me on the interview is: What is numerical complexity of summing all elements from vector and what from the list? What is real life difference in performance? Why difference exists? And most people get it right: vector has higher performance because accessing memory in linear fashion is faster than accessing scattered elements of list. It is sometimes less obvious why exactly contiguous access is faster, but this is a topic for another discussion. How to make code cache friendly than? Few examples:

- Keep things local. Data used together should be located closely in memory

- Keep things small. Compact data gives better yield per memory throughput unit

- Avoid indirectness. Pointer to object means another, usually distant, memory location needs to be loaded to cache. Although it sometimes goes against OO paradigms, Composition is usually more cache friendly than Aggregation

- If everything else fails: prefetch data ahead of time

So let’s start with real-life example of…

Keeping things small

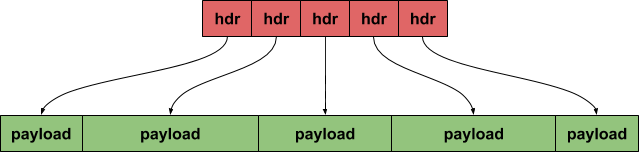

Imagine we have very fast network interface, able to deliver/consume 150 millions packets per second (yes, there is stuff that does that and even more). One data layout that can be used here are small packet descriptors containing, among other things, pointers to payload. This approach has some advantages and some disadvantages, which deserve post of its own. But for now assume this is the way. It will look something like that:

Let’s say that our imaginary header itself is struct defined as follows:

struct PacketDescriptor {

uint8_t physicalPort;

uint64_t timestampNs;

uint16_t size;

uint8_t* payload;

uint8_t isValid:1;

uint8_t flag2:1;

uint8_t flag3:1;

uint64_t payloadHash;

};

Nothing unexpected here:

- physical port on NIC

- timestamp in nanoseconds

- payload length

- payload pointer

- isValid and some other flags (not named, blame my lack of imagination)

- payload hash (because why not!)

Size of structure is 48 bytes. As it turns out it is quite important! Now let’s delve deeper, imagine two “processing” cases:

Receive (RX):

- Sum up all lengths if flag_valid is set to true

- Count all packets on port 3

Transmit (TX):

- Set timestamp with 100ns intervals

- Distribute packets over 4 ports

- Set flag “valid” to false if packet size is less than 64 bytes

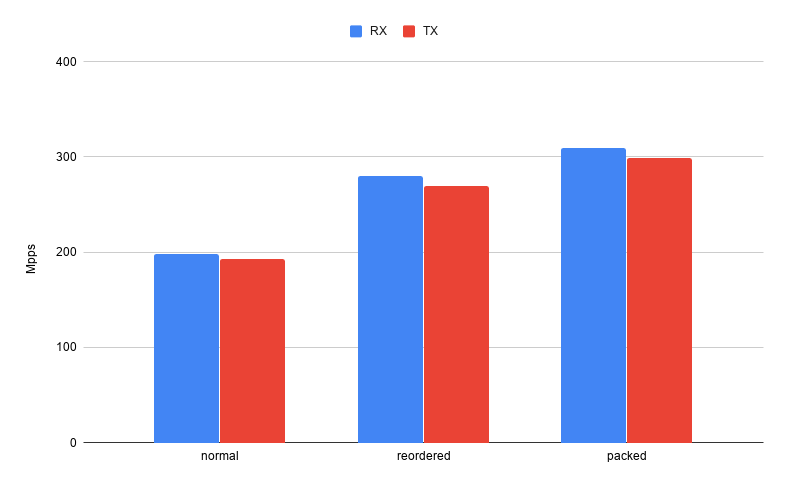

How fast can we do that? More or less optimal implementation can be found here. Running it on Xeon Gold 6148 gives result 198 Mpps (millions packets per second) for RX processing and 193 Mpps for TX processing. Can we do better than that?

Padding, alignment and reordering

Members of C/C++ structures are usually aligned to its size, uint16_t to 2, uint64_t to 8 etc. So this is how our structure is actually represented in memory:

struct PacketDescriptor

{

uint8_t txPort;

uint8_t pad1[7]; //<------

uint64_t timestampNs;

uint16_t length;

uint8_t pad2[6]; //<------

uint8_t* payload;

uint8_t flag_valid:1;

uint8_t flag2:1;

uint8_t flag3:1;

uint8_t pad3[7]; //<------

uint64_t payloadHash;

};

Quite a lot of wasted memory (and bandwidth) isn’t it? Fix for that would be just clever reordering fields in structure, in a way that all padding space is used. Simple heristic is to sort members by size:

struct PacketDescriptor_reordered {

uint64_t timestampNs;

uint8_t* payload;

uint64_t payloadHash;

uint16_t size;

uint8_t physicalPort;

uint8_t valid:1;

uint8_t flag2:1;

uint8_t flag3:1;

};

Size of our new structure is only 32 bytes. Now running exactly the same processing implementation gives 280 Mpps RX and 269 Mpps TX. It is clearly visible that even using exactly the same processing, without any algorithm optimization, just by optimizing data layout we got over 40% performance boost. Encouraged by that result: can it get even better?

Pack your data

Even when padding between struct members is eliminated, there still seems to be some overhead. Sum of all data members on 64bit machine is:

8 + 8 + 8 + 2 + 1 + 1 = 28 bytes

but sizeof() returns 32. Where additional 4 bytes comes from? Structures in C++ are aligned itself to alignment of its biggest member. So in this case to 8 bytes, and next 8-alignment for 28 will be 32. Fortunately there is a way to avoid this kind of padding by using type attribute packed on our descriptor structure. What it does? According to gcc manual it specifies that

each structure member is placed to minimize the memory required.

Which in short term means: remove all padding. This is how declaration of our structure looks now:

struct PacketDescriptor_packed {

(...)

} __attribute__((packed));

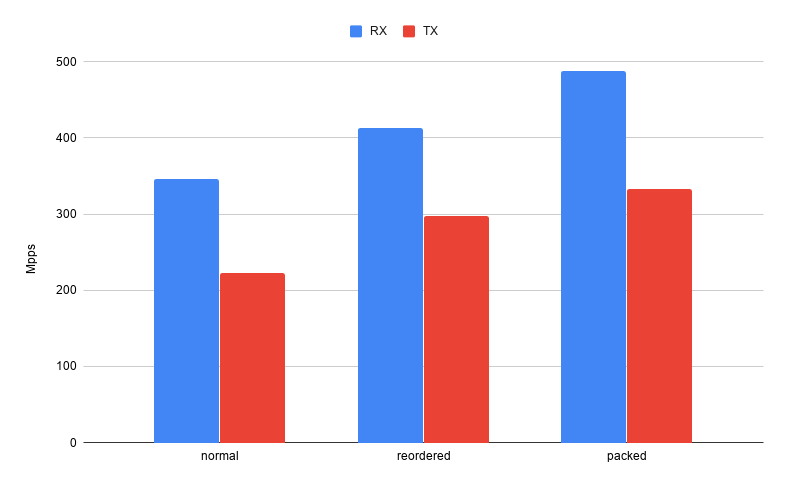

Reported size is indeed 28 bytes and performance was improved to 309 mpps RX and 299 mpps TX. Unfortunately nothing comes for free. Depending on CPU architecture it might be more expensive to extract unaligned data. Reading bitfields requires some shifting and masking done by CPU. And to make things worst on most CPUs there is quite substantial penalty for reading from unaligned addresses. In some cases all performance improvement can be diminished by this factor.

So to sum up, performance characteristics for all cases covered so far looks like that

Xeon Gold 6148

Intel i7-6700HQ

Is there more to that?

So it looks that there is very real, measurable benefit from reducing the size of data to process in both memory consumption and performance. But it goes even further, in the next part I will show more unordinary (but also complex and obscure) methods for further reducing hot data size.

Comments